In Episode 801 of Modern Wisdom, George Mack shares a concept called “Subprime Audiences.”

It’s a nod to the subprime mortgage crisis (2007-2010). Let me over-simplify it: the banks labeled a bunch of high-risk mortgages as “prime” (aka good), but they were not. It turned out they were “subprime” (aka bad). When reality caught up, the whole thing exploded.

As Margot Robbie said in The Big Short, “Whenever you hear subprime, think shit.”

According to Mack, you can apply this “subprime / shit” concept to social media audiences. Creators make the poor choice to publish content they, themselves, wouldn’t consume. They chase metrics. They make clickbait thumbnails that might attract assloads of viewers, but those views aren’t high-quality. The audience they build isn’t like them.

Thanks to incentives, they’re caught on a treadmill making content they don’t like… for audiences they don’t like. Eventually, the audience doesn’t like them either. Oops.

But I think the “subprime audience” situation is worse than that. Trying to reach audiences through social media is inherently broken. (And not only because of algorithmic feeds. That’s another rant.)

You might think you have a prime audience. But you probably don’t. You most likely have low-value activities (likes) that don’t convert to high-value activities (sales).

(That is… if you’re trying to build a business.)

Likes make us feel good, but they’re a weak indicator of interest.

That’s because it doesn’t cost anything to click “like.” It’s not a replacement for a real-world transaction because no one trades something in return for the thing you posted. There’s no actual exchange of value. (If people only walk into your store and say, “I LIKE your store,” and never buy anything, no matter how many people do it, your store is closing.)

50 or 100 or 1000 or 10,000 likes aren’t dollars (or even pennies, or even fractions of pennies). It’s only in VERY large quantities that likes can be considered worth anything at all.

And that’s only when those likes might lead to something that leads to something else that might someday lead to income.

Likes are too many speculative steps away from becoming something of value — such as groceries.

There’s that exhausted joke among artists and musicians: “It’s an excellent opportunity for promotion.” (Promotion of what? Your willingness to work for free?)

There’s a similar “subprime audience” problem with YouTube views.

Mack points out that too many YouTubers optimize for width instead of depth: “There’s a big difference between this video got played 10 million times, and this video got played a thousand times by 100 people.”

Let’s clean up the math. Would you rather have a video that:

A – 1,000,000 people watched once or

B – 100,000 people watched ten times each?

The number of views is the same (1 million), but the second audience would be “prime.”

They’re more likely to stick around and care what you do next. And to pay you money. (Kevin Kelly called this concept 1000 True Fans.)

Bad news: most of us who try to play the YouTube monetization game would never agree to work that many hours for a company in return for such shitty pay.

Here’s my experience: from 2022 to 2023, I made 56 episodes of The Carl King Show, each taking me about 20 hours of work. That’s a total of 1,120 hours.

How much money did YouTube pay me?

$156.

That’s 14 cents an hour. If you round up to the nearest penny. (Before taxes.)

Those 56 episodes were a hurricane of effort. It was a continual part-time job of thinking, writing, filming, and editing. If I spent that time as a minimum-wage fast food employee at $20/hour, I would have earned $22,400.

That’s a little better than $156.

But it’s horrifically less than I would make doing that same video production work for a client.

My YouTube channel has 16,500 watch hours and 322,000 views. That means my average view is 3.07 minutes. Considering my episodes were maybe 40 minutes on average, either I’m bad at what I do…

…or there’s simply not a big enough audience for it anyway.

(To be fair, my approach was academic rather than entertaining. I probably would have been better off packaging it as a book or online course. Which I’m considering…)

Multiply those poor results by every “creator” like me, and you’ve got vast amounts of time and energy evaporating from the economy.

But not really. Where does some of it go?

2023 Revenue:

Facebook / Instagram / Meta – $134,000,000,000

YouTube – $31,500,000,000

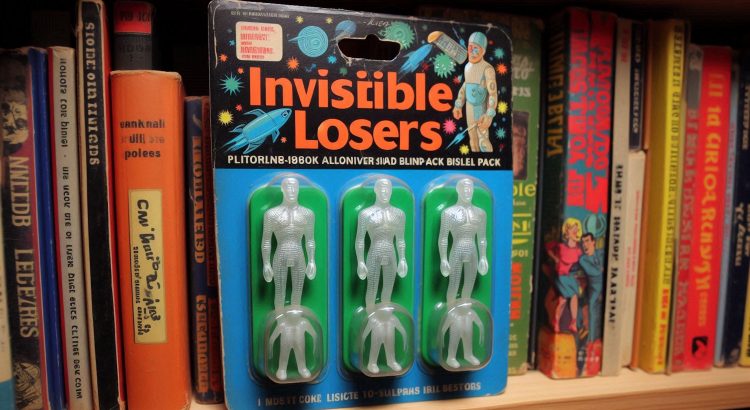

“But Carl, some people earn a lot of money making YouTube videos!” Yes, some do. They’re the winners, and they’re visible. Guess who’s invisible? The losers.

This phenomenon is called Survivorship Bias. It’s called that because only the winners “survive” the process. The losers die off. So when we see our favorite YouTube personalities doing their thing every week, we assume it can’t really be that hard to do.

Take a stadium. Put all the YouTube winners on one side and the YouTube losers on the other. I suspect most of the losers would see those odds clearly and give up.

According to a “Certified YouTube Expert” named Alan Spicer, 99.75% of YouTube Creators make ZERO money.

https://alanspicer.com/what-percentage-of-youtubers-make-money

What a promising line of work! That’s 399 out of 400 people working for YouTube for free. Only one of those makes at least a penny.

I don’t know how many make a livable wage, but it’s got to be, uh, exponentially fewer.

I’d love to behold that stadium full of losers. Unfortunately, no stadium is big enough. (There are 63.8 million YouTube creators, and we know which side of the stadium would be full.)

One thing is for sure — the advertisements will keep running. Doesn’t matter who makes the content, what that content is, or how short the views are. Just keep on uploading it, losers.

Imagine how much better off we’d be — how much tangible value we could create — if we:

1 – stopped scrolling and watching advertisements for 4 hours a day and

2 – spent our time earning guaranteed money in the real world instead of creating free content for social media companies.

But creative people will always get tricked into working for free. More than we like money, we fear obscurity—and social media companies know this.