I’ve been reading a lot. Mostly non-fiction. My favorite topics are critical thinking, decision-making, and money. I’m old and lazy, so I appreciate ideas that make my life easier. (And since I like writing, I also read a ton of “books about writing” but those are for another time.)

I prefer the digital (specifically Kindle) format because of the highlighting feature. Once I finish a book, I go back and review all my highlights. It helps me retain — and also locate those concepts in the future. It’s scary how much goes in one eye and out the other.

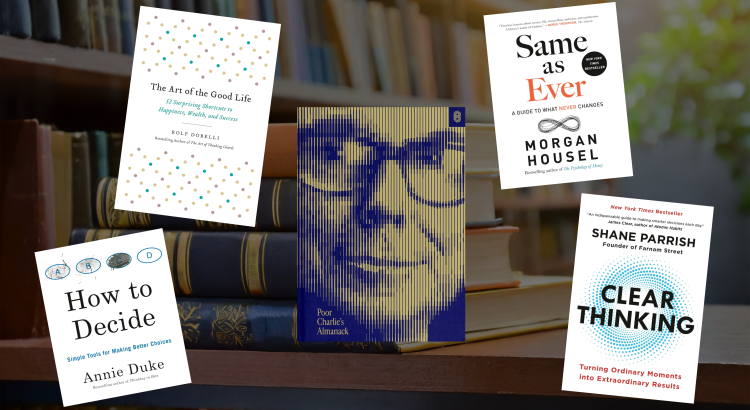

Here are five recent books I’ve read and a highlight from each. Disclaimer: these contain affiliate links.

How To Decide by Annie Duke

“Smart people often think more highly of their beliefs and opinions. They are less likely to think the stuff they know needs correcting. They have more confidence in what their intuition or gut tells them. After all, they’re really smart. Why wouldn’t they have more confidence in those things? When you’re smart, you’re naturally less skeptical about the things you believe to be true. Smart people are also better at constructing convincing arguments that support their views and reinforce the things they believe to be true. Smart people are better at spinning narratives that convince other people that they are right, not in the service of misleading those people but in the service of keeping the fabric of their own identity from tearing.”

Poor Charlie’s Almanack by Charlie Munger

“Even man’s minor possessions tend to be over-appraised. Once owned, they suddenly become worth more to him than he would pay if they were offered for sale to him and he didn’t already own them. There is a name in psychology for this over-appraise-your-own-possessions phenomenon: the endowment effect. All man’s decisions are suddenly regarded by him as better than would have been the case just before he made them.”

Same As Ever by Morgan Housel

“Another point about long-term thinking is how it sways the information we consume. I try to ask when I’m reading: Will I care about this a year from now? Ten years from now? Eighty years from now? It’s fine if the answer is no, even a lot of the time. But if you’re honest with yourself you may begin to steer toward the more enduring bits of information. There are two types of information: permanent and expiring. Permanent information is: “How do people behave when they encounter a risk they hadn’t fathomed?” Expiring information is: “How much profit did Microsoft earn in the second quarter of 2005?” Permanent information is harder to notice because it’s buried in books rather than blasted in headlines. But its benefit is huge.”

Clear Thinking by Shane Parrish

“The problem is, our default behavior often makes things worse. When someone slights us, we lash out with angry words. When someone cuts us off, we assume malice on their part. When things go slower than we want, we become frustrated and impatient. When someone is passive-aggressive, we take the bait and escalate. In these moments of reaction, we don’t realize that our brains have been hijacked by our biology, and that the outcome will go against what we seek. We don’t realize that hoarding information to gain an advantage is hurting the team. We don’t realize we’re conforming to the group’s ideas when we should be thinking for ourselves. We don’t realize our emotions are making us react in ways that create problems downstream. So our first step in improving our outcomes is to train ourselves to identify the moments when judgment is called for in the first place, and pause to create space to think clearly. This training takes a lot of time and effort, because it involves counterbalancing our hardwired biological defaults evolved over many centuries. But mastery over the ordinary moments that make the future easier or harder is not only possible, it’s the critical ingredient to success and achieving your long-term goals.”

The Art of the Good Life by Rolf Dobelli

“If you want to help reduce suffering on the planet, donate money. Just money. Not time. Money. Don’t travel to conflict zones unless you’re an emergency doctor, bomb-disposal expert or diplomat. Many people fall for the volunteer’s folly—they believe there’s a point to voluntary work. In reality, it’s a waste. Your time is more meaningfully invested in your circle of competence (Chapter 14), because it’s there that you’ll generate the most value per day. If you’re installing water pumps in the Sahara, you’re doing work that local well-diggers could carry out for a fraction of the cost. Plus, you’re taking work away from them. Let’s say you could dig one well per day as a volunteer. If you spent that day working at your office and used the money you earned to pay local well-diggers, by the end of the day you’d have a hundred new wells. Sure, volunteering makes you feel good, but it shouldn’t be about that. And that warm Good Samaritan glow is based on a fallacy. The first-rate specialists on site (Médecins Sans Frontières, the Red Cross, UNICEF, etc.) will put your donations to more effective use than you could yourself. So work hard and put your money in the hands of professionals.”